| Secret subway Author: Corey, Shana | ||

| Price: $6.50 | ||

Summary:

In 1870, Alfred Ely Beach invents New York's first underground train.

| Accelerated Reader Information: Interest Level: LG Reading Level: 4.30 Points: .5 Quiz: 180814 | Reading Counts Information: Interest Level: K-2 Reading Level: 4.30 Points: 2.0 Quiz: 68635 | |

Reviews:

Kirkus Reviews (+) (01/01/16)

School Library Journal (01/01/16)

The Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books (+) (04/16)

Full Text Reviews:

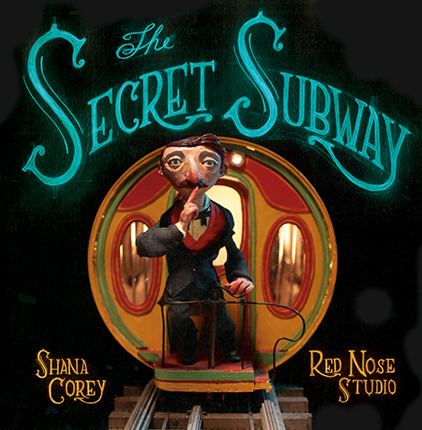

School Library Journal - 01/01/2016 K-Gr 3—This picture book tells the story of Alfred Ely Beach, whose Beach Pneumatic Transit was an early version of the New York subway, which was eventually abandoned to the shadows of history. The story begins, "Welcome to New York City—the greatest city on earth!" The fervent pace continues throughout. The artwork is intriguing: photographs of puppetlike polymer figures are shown talking while cartoon ideas emanate from their mouths. Often, white text is set on a black background, creating an underground feel. A fact spread is appended, revealing more of Beach's life. Keen artwork combines with inviting language, illuminating an obscure part of New York City's history. VERDICT Perfect for young subway enthusiasts, especially those with an interest in New York City.—Anne Chapman Callaghan, Racine Public Library, WI - Copyright 2016 Publishers Weekly, Library Journal and/or School Library Journal used with permission.

Bulletin for the Center... - 04/01/2016 “The Sidewalks of New York” already dripped nostalgia when the song was penned in the 1890s, and decades earlier, pedestrians would has been hard-pressed to trip the light fantastic on their traffic-tangled, refuse-strewn street system. Alfred Ely Beach figured out a solution: move the pedestians below street level, accommodate them in comfortable cars, and propel the cars through pneumatic tubes. But then as now, a promising idea can run afoul of bureaucracy and politics, and Beach’s clever end run around these obstacles goes down in history—and in Corey’s delightful picture book—as an example of gleeful “Told you so!” vindication. The main text traces, and an author’s note explicates, the outline of the subway story. Beach’s concept of a pneumatic-powered underground system for human passengers was floated and hailed at New York’s American Institute Fair in 1867, but legal arcana made permission to realize the project unlikely. A smaller pneumatic mail tube system could be pushed through, though, and while Beach officially worked on the that project, a second clandestine excavation was underway, boring far beneath street level from its origin below Devlin’s Clothing Store, to its terminus nearly a hundred yards away. By early 1870, Beach’s demo car and station were a done deal, and a party of New York A-listers were invited to descend to a well-furnished subterranean waiting room to admire, and later board, the ride of the future. “All winter, while wagons slipped and slid on the slushy streets above, people poured into Devlin’s for the twenty-five cent ride. It looked as though Beach’s plan was going to work.” Inarguably, it did work, but pushback from street-level merchants (what, no foot traffic?) and the politicians they supported doomed any scaled-up expansion; it would be over three decades before New York was officially ready to accept an underground transit system. Corey’s narration brings plenty of sparkle to a story built on stealth and shadows. The account of Beach’s project is shaped to maximize the contrast between the sensible solution to a crying need, and the cumbersome and even shady forces holding back progress, with Beach solidly cast in the role of trickster hero. The narrative flow—with assist from snippets of imagined public comment and precisely deployed upper-case font—is a readaloud tour de force: “From politicians to peddlers, street sweepers to scientists, everyone had ideas. . . . ‘What about building double-decker roads?’ ‘Or a railway on stilts?’ But no matter how much everyone talk-talk-TALKED, nothing ever seemed to get off the ground.” Obviously, not every child will race to embrace a historical vignette on invention stymied by bureaucracy, but rely on Red Nose Studio’s visual pizzazz to lure them through the turnstile. Fans of Jonah Winter and Red Nose’s Here Comes the Garbage Barge! (BCCB 4/10), another wry chronicle of bureaucratic ball-dropping, will immediately recognize the medium: photographs of intricately staged scenes comprising found and built objects and populated with posable mannequins, several of which boast interchangeable baked clay heads that can be switched out as facial expression demands. Any kids (or overinvolved parents) who have attempted dioramas for school assignments will recognize the gold standard here and bow down in the presence of genius. A warm glow illuminates the scene in which Beach hatches his idea, turning a crank on a Rube Goldbergian apparatus with one hand, while a black ink drawing of a tube-like subway car emerges from the crown of his top hat. Most scenes, though, emerge stealthily from eerie light in underground shadow, as grubby workers haul away carts of excavation debris in the dead of night, and prominent citizens scurry down a darkened stairway for the subway debut. In a spread on the inside of the dust jacket, Chris Sickel of Red Nose Studio shares with readers how he created his artwork from research to construction, and viewers will enjoy comparing his work-in-progress illustrations with the final product. That is . . . if technical services hasn’t tossed out or taped down the dust jacket. It might be worth procuring an extra copy for the poster art, or perhaps as an inspiration for multi-age library programming. (See p. 410 for publication information.) Elizabeth Bush, Reviewer - Copyright 2016 The Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois.