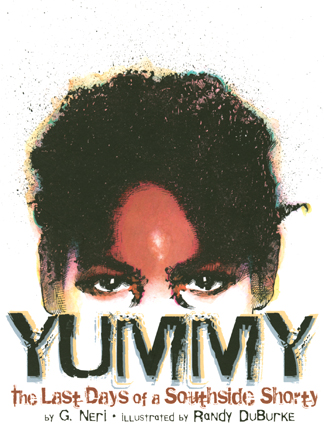

Full Text Reviews: Bulletin for the Center... - 09/01/2010 What do you call an eleven-year-old gang assassin? A predator or a victim? In this graphic novel Neri reconstructs the events surrounding the brief life of Robert “Yummy” Sandifer, a neglected and abused Chicago child who, after committing a string of felonies in 1994, shot teen bystander Shavon Dean, dodged the police for several days, and was ultimately executed by members of his own gang, the Black Disciples. Yummy’s story, which became a national media flashpoint, may seem like ancient history to prospective readers born years after the murders, and the veneer of fiction supplied here (fictional Roseland resident Roger, also age eleven, tells about the neighborhood incident and worries about his own older brother, who is a known gang member) has the look of edgy urban lit. But author’s notes and an appended bibliography (with the cited Time article “Crime: Murder in Miniature” readily available online) assure readers this is the real deal. Comics illustrator DuBurke’s gritty black-and-white artwork employs foreshortened backgrounds to bring the action right up in the reader’s face, whether it’s talking heads calmly discussing their theories on Yummy’s disordered personality, families in mourning, or a semiautomatic pointed directly out of the frame. Call it historical fiction to be technically correct, but for kids who still grow up believing that “you make it past 19 these days, you a senior citizen around here,” it’s heartbreakingly contemporary. EB - Copyright 2010 The Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. School Library Journal - 09/01/2010 Gr 7 Up—In 1994, an incident of Southside Chicago gang-related violence captured national headlines. Eleven-year-old Robert "Yummy" Sandifer shot and killed his 14-year-old neighbor Shavon Dean. Neri's retelling is based on public records as well as personal and media accounts from the period. Framing the story through the eyes and voice of a fictional character, 11-year-old Roger, offers a bittersweet sense of authenticity while upholding an objective point of view. Yummy, so named because of his love of sweets, was the child of parents who were continually in prison. While living legally under the care of a grandmother who was overburdened with the custody of numerous grandchildren, Yummy sought out the closest thing he could find to a family: BDN or Black Disciples Nation. In the aftermath and turmoil of Shavon's tragic death, he went into hiding with assistance from the BDN. Eventually the gang turned on him and arranged for his execution. The author frames the story with this central question: Was Yummy a cold-blooded killer or a victim of his environment? While parts of the message focusing on the consequences of choice become a little heavy-handed, the exploration of "both sides of the story" is unflinchingly offered. In one of the final panels, narrator Roger states, "I don't know which was worse, the way Yummy lived or the way he died." Realistic black-and-white art further intensifies the story's emotion. A significant portion of the panels feature close-up faces. This perspective offers readers an immediacy as well as emotional connection to this tragic story.—Barbara M. Moon, Suffolk Cooperative Library System, Bellport, NY - Copyright 2010 Publishers Weekly, Library Journal and/or School Library Journal used with permission. Booklist - 08/01/2010 *Starred Review* Robert Sandifer—called “Yummy” thanks to his sweet tooth—was born in 1984 on the South Side of Chicago. By age 11 he had become a hardened gangbanger, a killer, and, finally, a corpse. In 1994, he was a poster child for the hopeless existence of kids who grow up on urban streets, both victims and victimizers, shaped by the gang life that gives them a sense of power. Neri’s graphic-novel account, taken from several sources and embellished with the narration of a fictional classmate of Yummy’s, is a harrowing portrait that is no less effective given its tragic familiarity. The facts are laid out, the suppositions plausible, and Yummy will earn both the reader’s livid rage and deep sympathy, even as the social structure that created him is cast, once again, as America’s undeniable shame. Tightly researched and sharply written, if sometimes heavy-handed, the not-quite-reportage is brought to another level by DuBurke’s stark black-and-white art, which possesses a realism that grounds the nightmare in uncompromising reality and an emotional expressiveness that strikes right to the heart. Like Joe Sacco’s work (Footnotes in Gaza, 2010), this is a graphic novel that pushes an unsightly but hard to ignore sociopolitical truth out into the open. - Copyright 2010 Booklist. Loading...

|