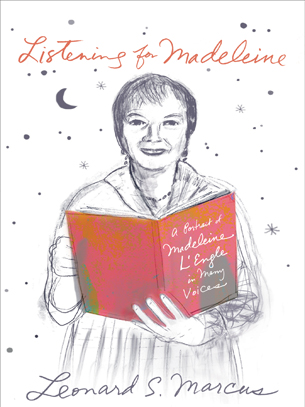

Listening for Madeleine

Listening for Madeleine: A Portrait of Madleine L’Engle in Many Voices by Leonard S. Marcus. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012. 384 pages.

Listening for Madeleine: A Portrait of Madleine L’Engle in Many Voices by Leonard S. Marcus. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012. 384 pages.

Cast aside your preconception of what a biography should be when picking up Listening for Madeleine: A Portrait of Madeleine L’Engle in Many Voices by Leonard S. Marcus. Now, take a moment to recall the 80s fad for creating portraits from hundreds and sometimes thousands of tiny pictures. Step away, you see the whole picture with shadings of light and dark, a recognizable image of an icon. Step closer and each intimate face is revealed. This is Listening for Madeleine.

Marcus conducted dozens of interviews, all but two in person, with people who could give insights into the many personas of L’Engle: Writer, Matriarch, Mentor, Friend, and Icon. Marcus begins with “Madeleine in the Making,” giving us childhood snapshots that show us a lonely child whose parents were often absent, the socially and physically awkward girl, and, later, the young woman who worked with the great actress Eva La Galliene and had her first published piece while still in college. This masterful essay gives us the frame for the picture within, context for each subsequent vignette.

This is not a book for those who wish to continue to regard the author with worshipful reverence. L’Engle’s flaws are all too real as are the tragedies in her life. The impact of alcoholism on the men closest to Madeleine throughout her life gives Meg’s urgent quest to find her father a fresh poignancy.

Perhaps the best benefit to the reader is discovering the many different aspects of her writing life. Fans of A Wrinkle in Time may be oblivious to her Crosswicks Journals. While those who admire her religious writings may have missed the spiritual underpinnings of her novels.

Best of all are the nuggets– and there are many– that reveal the author and mentor at work. Editors Sandra Jordan and Stephen Roxburgh recount their own experiences with insightful details. Roxburgh’s memories of himself as a neophyte editor are summed up in his comment that “New editors need old writers and new writers need old editors.” Catherine Hand worked to get the film adaptation of Wrinkle for years and the process revealed what Madeleine considered to be the heart of her classic: “Like and equal are not the same.” A short piece by Patricia Gauch foreshadows a longer conversation with T.A. Barron who recounts how L’Engle championed the young author. When a math professor dines with Madeleine and her husband, actor Hugh Franklin, he asks at the end of the evening for both Madeleine and Hugh to sign his copy of Wrinkle in Time. Hugh disclaims, saying he did not really have a part in the book. “That’s not true,” exclaims Madeleine. “You’re my Calvin.” In this moment, as in so many others, she leaps off the page and becomes a living, breathing human being.

The portrait that emerges from Listening to Madeleine is of a person who was perfectly imperfect. As we see glimpses of the author, the grande dame, the entertainer (and the story of an ALA presentation from the point of view of a cocky co-panelist is particularly disarming), the pragmatist, and the spiritual guide, we become part of the story ourselves, feeling that we, too, have an idea of what it must have been like to be Madeleine L’Engle’s friend.

– Reviewed by Ellen Myrick